Tuesday, May 15, 2012

It's So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

WHY BAD?!?

The inspiration:

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

fallacies,

videos

Sunday, April 29, 2012

B.S.

Here's the video of Jon Stewart interviewing Harry Frankfurt about his book On Bullshit (which you can read online for free here).

What do you think? Is not caring about whether you're telling the truth worse than deliberately lying?

What do you think? Is not caring about whether you're telling the truth worse than deliberately lying?

Saturday, April 28, 2012

Final Exam

Just a reminder: the final exam is Tuesday, May 1st. For the 8:00 class, the final is from 8:00-10:00 a.m., and for the 9:25 class, it is from 10:15 a.m.-12:15 p.m.

Friday, April 27, 2012

Last Chance

Just a reminder that the course evaluation for this class is only open two more days (today and tomorrow). If you haven't done it yet, go do it! Here are instructions:

1. Go to http://cp.rowan.edu/cp/.

2. Click "Student Self-Service" icon.

3. Click "Access Banner Services - Secure Area - login required"

4. Enter User ID and PIN.

5. Click "Personal Information".

6. Click "Answer a Survey".

7. Click on one of the student evaluations for your classes.

8. Complete the student evaluation.

9. Click “Survey Complete” to submit your completed student evaluation.

10. Repeat for other Spring 2012 classes.

Thursday, April 26, 2012

Open-mindedness

Here's an entertaining 10-minute video on open-mindedness, science, and paranormal beliefs.

I like the definition of open-mindedness offered by this video: it is being open to new evidence. This brings with it a willingness to change your mind... but only if new evidence warrants such a change.

Changing your mind has gotten a bum rap lately: flip-flopping can kill a political career. But willingness to change your mind is an important intellectual virtue that is valued by scientists.

I like the definition of open-mindedness offered by this video: it is being open to new evidence. This brings with it a willingness to change your mind... but only if new evidence warrants such a change.

Changing your mind has gotten a bum rap lately: flip-flopping can kill a political career. But willingness to change your mind is an important intellectual virtue that is valued by scientists.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

I'M-SPECIAL-ism,

intellectual honesty,

links,

psychological impediments

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

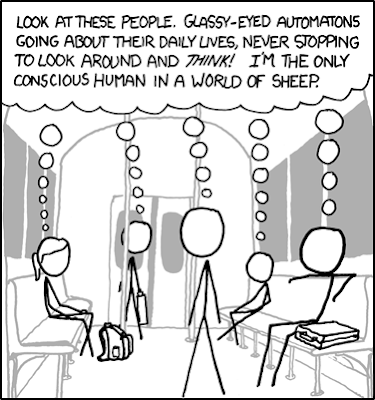

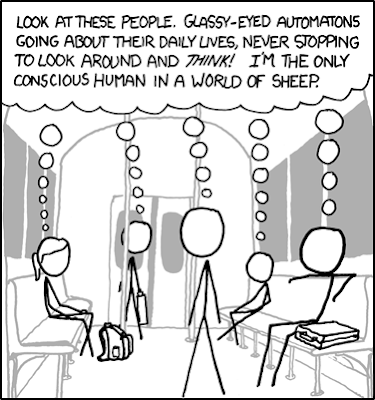

Intellectual Humility

I think there’s an important connection between intellectual honesty and humility. A simple goal of this class is to get us all to recognize what counts as good evidence and what counts as bad evidence for a claim. I think we've gotten pretty good at this so far. But this doesn’t guarantee that we’ll care about the difference once we figure it out.

Getting us to care is the real goal. We should care about good evidence. We should care about evidence and arguments because they get us closer to the truth. When we judge an argument to be overall good, THE POWER OF LOGIC COMPELS US to believe the conclusion. If we are presented with decent evidence for some claim, but still stubbornly disagree with this claim for no strong reason, we are just being irrational. Worse, we’re effectively saying that the truth doesn’t matter to us.

Instead of resisting, we should be open-minded. We should be willing to challenge ourselves--seriously challenge ourselves--and allow new evidence change our current beliefs if it warrants it. We should be open to the possibility that we’ve currently gotten something wrong. This is how comedian Todd Glass puts it:

Here are the first two paragraphs of an interesting article on this:

Getting us to care is the real goal. We should care about good evidence. We should care about evidence and arguments because they get us closer to the truth. When we judge an argument to be overall good, THE POWER OF LOGIC COMPELS US to believe the conclusion. If we are presented with decent evidence for some claim, but still stubbornly disagree with this claim for no strong reason, we are just being irrational. Worse, we’re effectively saying that the truth doesn’t matter to us.

Instead of resisting, we should be open-minded. We should be willing to challenge ourselves--seriously challenge ourselves--and allow new evidence change our current beliefs if it warrants it. We should be open to the possibility that we’ve currently gotten something wrong. This is how comedian Todd Glass puts it:

Here are the first two paragraphs of an interesting article on this:

Last week, I jokingly asked a health club acquaintance whether he would change his mind about his choice for president if presented with sufficient facts that contradicted his present beliefs. He responded with utter confidence. “Absolutely not,” he said. “No new facts will change my mind because I know that these facts are correct.”Ironically, having extreme confidence in oneself is often a sign of ignorance. Remember, in many cases, such stubborn certainty is unwarranted.

I was floored. In his brief rebuttal, he blindly demonstrated overconfidence in his own ideas and the inability to consider how new facts might alter a presently cherished opinion. Worse, he seemed unaware of how irrational his response might appear to others. It’s clear, I thought, that carefully constructed arguments and presentation of irrefutable evidence will not change this man’s mind.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

I'M-SPECIAL-ism,

intellectual honesty,

links,

more cats? calm down sean,

psychological impediments

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

Class Canceled (4/24)

I am sick again, so our class is canceled for today (Tuesday, April 24th). Sorry for the late notice.

Homework #3 is still due at the beginning of class on Thursday April 26th.

Homework #3 is still due at the beginning of class on Thursday April 26th.

Practical Advice

How can we counteract these cognitive biases we're learning about? Examining the way we think and becoming more aware of our biases is a good start, but is not in itself a solution.

One big point is to own our fallibility. Awareness of our limits and biases should lead us to lower our degree of confidence in many of our beliefs--particularly deeply held opinions and stances on controversial issues. Simply put, we should get in the habit of admitting (and sincerely believing) that there's a real chance that we're wrong.

Here are two other big, simple points I think make for some great practical advice:

One big point is to own our fallibility. Awareness of our limits and biases should lead us to lower our degree of confidence in many of our beliefs--particularly deeply held opinions and stances on controversial issues. Simply put, we should get in the habit of admitting (and sincerely believing) that there's a real chance that we're wrong.

Here are two other big, simple points I think make for some great practical advice:

- Get Unfamiliar! A

ctively seek out sources that you disagree with. We tend to surround ourselves with like-minded people and consume like-minded media. This hurts our chances of discovering that we've made a mistake. In effect, it puts up a wall of rationalization around our preexisting beliefs to protect them from any countervailing evidence.

ctively seek out sources that you disagree with. We tend to surround ourselves with like-minded people and consume like-minded media. This hurts our chances of discovering that we've made a mistake. In effect, it puts up a wall of rationalization around our preexisting beliefs to protect them from any countervailing evidence. - Focus on What Hurts! When we do check out our opponents, it tends to be the obviously fallacious straw men rather than sophisticated sources that could legitimately challenge our beliefs. But this is bad! We should focus on the best points in the arguments against what you believe. Our opponents' good points are worth more attention than their obviously bad points. Yet we often focus on their mistakes rather than the reasons that hurt our case the most.

Monday, April 23, 2012

Changing Habits

"If you want to change a habit, …don’t try and change everything at once. Instead, figure out what the cue is, figure out what the reward is and find a new behavior that is triggered by that cue and delivers that same reward. "

— Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit, on Fresh Air

Less Wrong has several great posts on effective techniques for breaking bad habits and replacing them with better ones:

- The Science of Rationality

- Scientific Self-Help: The State of Our Knowledge

- Build Small Skills in the Right Order

- How to Beat Procrastination

Metacognition

There's a name for all the studying of our natural thinking styles we've been doing in class lately: metacognition. When we think about the ways we think, we can vastly improve our learning abilities. This is what the Owning Our Ignorance club is about.

There's a name for all the studying of our natural thinking styles we've been doing in class lately: metacognition. When we think about the ways we think, we can vastly improve our learning abilities. This is what the Owning Our Ignorance club is about.I think this is one of the most valuable concepts we're learning all semester. So if you read any links, I hope it's these two:

Sunday, April 22, 2012

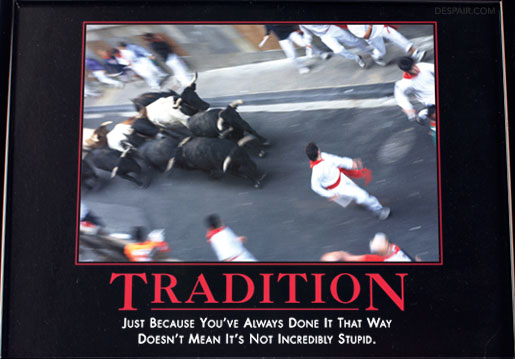

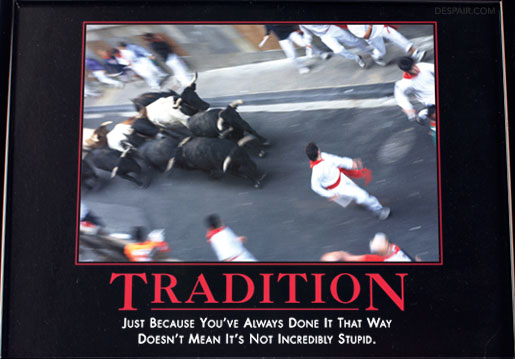

Status Quo Bias

Lazy, inert humans:

- If it already exists, we assume it's good.

- Our mind works like a computer that depends on cached responses to thoughtlessly complete common patterns.

- NYU psychologist John Jost does a lot of work on system justification theory. This is our tendency to unconsciously rationalize the status quo, especially unjust social institutions. Scarily, those of us oppressed by such institutions have a stronger tendency to justify their existence.

- Jost has a new book on this stuff. Here's a video dialogue about his research:

Saturday, April 21, 2012

Let's All Nonconform Together

If you like these links, I'll let you in my exclusive club:

- On the influence of your in-groups and the formation of your identity: "If you want to set yourself apart from other people, you have to do things that are arbitrary, and believe things that are false." (from Paul Graham's "Lies We Tell Our Kids.")

- Here's a summary of two recent studies which suggest that partisan mindset stems from a feeling of moral superiority.

- Here's that poll showing the Republican-Democrat switcharoo regarding their opinion of Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke when the executive office changed parties.

- Our political loyalties also influence our view on the economy.

- Here's an article about a cool study on the relationship between risk and provincialism.

- Conformity hurts the advancement of science.

Friday, April 20, 2012

Paper Guideline

Due Date: the beginning of class on Tuesday, May 1st, 2012

Worth: 10% of final grade

Length/Format: Papers must be typed, and must be between 400-800 words long. Provide a word count on the first page of the paper. (Most programs like Microsoft Word & WordPerfect have automatic word counts.)

Assignment:

1) Pick an article from a newspaper, magazine, or journal in which an author presents an argument for a particular position.There are some links to potential articles here. I recommend choosing from those articles, though you are also free to choose an article on any topic you want.

PRO TIP: It’s easier to write this paper on an article with a BAD argument. Try finding a poorly-reasoned article!

If you don’t chose from the articles on the blog, you must show Sean your article by Tuesday, April 24th for approval. The main requirement is that the article present an argument. One place to look for such articles is the Opinion page of a newspaper. Here’s a short list of some other good sources:

Worth: 10% of final grade

Length/Format: Papers must be typed, and must be between 400-800 words long. Provide a word count on the first page of the paper. (Most programs like Microsoft Word & WordPerfect have automatic word counts.)

Assignment:

1) Pick an article from a newspaper, magazine, or journal in which an author presents an argument for a particular position.There are some links to potential articles here. I recommend choosing from those articles, though you are also free to choose an article on any topic you want.

PRO TIP: It’s easier to write this paper on an article with a BAD argument. Try finding a poorly-reasoned article!

If you don’t chose from the articles on the blog, you must show Sean your article by Tuesday, April 24th for approval. The main requirement is that the article present an argument. One place to look for such articles is the Opinion page of a newspaper. Here’s a short list of some other good sources:

- The New Yorker

- Slate

- New York Review of Books

- London Review of Books

- Times Literary Supplement

- Boston Review

- Atlantic Monthly

- The New Republic

- The Weekly Standard

- The Nation

- Reason

- Dissent

- First Things

- Mother Jones

- National Journal

- The New Criterion

- Wilson Quarterly

- The Philosophers' Magazine

2) In the essay, first briefly explain the article’s argument in your own words. What’s the position that the author is arguing for? What are the reasons the author offers as evidence for her or his conclusion? What type of argument does the author provide? In other words, provide a brief summary of the argument.

NOTE: This part of your paper shouldn’t be very long. I recommend making this only one paragraph of your paper.

3) In the essay, then evaluate the article’s argument. Overall, is this a good or bad argument? Why or why not? Systematically evaluate the argument:

- Check each premise: is each premise true? Are any false? Questionable? (Do research if you have to in order to determine whether the premises are true.)

- Then check the structure of the argument. Do the premises provide enough support for the conclusion?

- Does the argument contain any fallacies? If so, which one(s)? Exactly how does the argument commit it/them?

NOTE: This should be the main part of your paper. Focus most of your paper on evaluating the argument.

4) If your paper is not on one of the articles linked to on the course blog, attach a copy of the article to your paper when you hand it in. (Save trees! Print it on few pages!)

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

logistics

Thursday, April 19, 2012

Possible Paper Articles

Here are some links to a variety of articles you could use for your paper on explaining and evaluating an article's argument. I strongly recommend using one of these articles, since many (the first 8 in particular) contain bad arguments:

- Down With Facebook!: it's soooo lame

- Is Facebook Making Us Lonely? generational I'M-SPECIAL-ism

- Do Fish Feel Pain?: "it's a tricky issue, so I'll go with my gut"

- In the Basement of the Ivory Tower: are some people just not meant for college?

- Study Says Social Conservatives Are Dumb: but that doesn't mean they're wrong

- A New Argument Against Gay Marriage: hetero marriage is unique & indispensable

- Ben Stein's Confession for the Holidays: taking sides on the war on christmas

- Get Over Ferris Bueller: it's an overrated movie

- You Don't Deserve Your Salary: no one does

- The Financial Crisis Killed Libertarianism: if it wasn't dead to begin with

- How'd Economists Get It So Wrong?: Krugman says the least wrong was Keynes

- An Open Letter to Krugman: get to know your field

- Consider the Lobster: David Foster Wallace ponders animal ethics

- Are Dolphins People?: an ocean full of sea-people

- The Dark Art of Interrogation: Bowden says torture is necessary

- The Idle Life is Worth Living: in praise of laziness

- Should I Become a Professional Philosopher?: maybe not (update)

- Blackburn Defends Philosophy: it beats being employed

Homework #3: Advertisement

Homework #3 is due at the beginning of class on Thursday, April 26th. Your assignment is to choose an ad (on TV or from a magazine or wherever) and evaluate it from a logic & reasoning perspective.

- First, very briefly explain the argument that the ad offers to sell its product.

- Then, list and explain the mistakes in reasoning that the ad commits.

- Then, list and explain the psychological ploys the ad uses (what psychological impediments does the ad try to exploit?).

- Attach (if it's from a newspaper or magazine) or briefly explain the ad.

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

Wished Pots Never Boil

Here is a hodgepodge of links on some psychological impediments we're discussing recently:

- If you're a fan of The Secret, you should beware that it's basic message is wishful thinking run amok.

- Courtroom judges have pretty serious biases: they're more lenient earlier in the day and right after a break. Scary!!!!

- Teachers have biases, too: we're self-serving and play favorites.

- Why don't we give more aid to those in need? Psychological impediments are at least partly to blame.

- Why do we believe medical myths (like "vitamin C cures the common cold," or "you should drink 8 glasses of water a day")? Psychological impediments, of course!

- Wikipedia has a great list of common misconceptions.

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

Quiz You Twice, Shame on You

Quiz #2 will be held at the beginning of class on Thursday, April 19th. It will last 25 minutes, and is worth 7.5% of your overall grade. The quiz is on everything we've discussed since the midterm, including these fallacies:

- Appeal to Authority

- False Dilemma

- Slippery Slope

- The Naturalistic Fallacy

- Direct Experience

- Memory

- Anecdotal Evidence & Hearsay

- Confirmation & Disconfirmation Bias

- Statistical Biases

- Overconfidence (I'M-SPECIAL-ism)

- Social Pressures

Monday, April 16, 2012

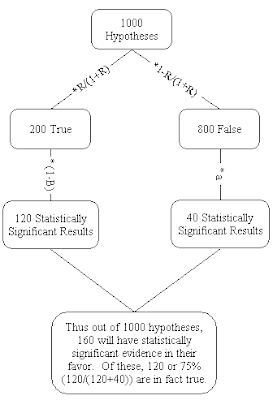

Most Published Science is False

Beware: as the flowchart above suggests, most published scientific research is probably false. Seriously, there's a pretty big decline effect problem in science.

This is why you should trust meta-analyses (scientific surveys of all the related studies on a particular issue) over any individual study. You should also trust settled science (the stuff you'd find in a textbook) more than any new scientific research. And you should be especially wary of any science explained on the news.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

authority,

links,

news,

psychological impediments

Sunday, April 15, 2012

The Smart Bias

Oddly, the I'M-SPECIAL-ism bias seems to increase the more intelligent you are. Studies suggest that the smarter and more experienced you are, the more overconfident you're likely to become. In particular, we seem to believe that our intelligence makes us immune to biases. But that's just not true! The philosopher Nigel Warburton puts it nicely:

“Many of us would like to believe that intellect banishes prejudice. Sadly, this is itself a prejudice.”

Saturday, April 14, 2012

No, I'm Not

One of my favorite topics is I'M-SPECIAL-ism. Psychological research has repeatedly shown that most Americans overestimate their own abilities. This is one of the biggest hurdles to proper reasoning: the natural tendency to think that I'm more unique--smarter, or more powerful, or prettier, or whatever--than I really am.

You may have noticed that one of my favorite blogs is Overcoming Bias. Their mission statement is sublimely anti-I'M-SPECIAL-ist:

So I hope you'll join the campaign to end I'M-SPECIAL-ism.

You may have noticed that one of my favorite blogs is Overcoming Bias. Their mission statement is sublimely anti-I'M-SPECIAL-ist:

"How can we better believe what is true? While it is of course useful to seek and study relevant information, our minds are full of natural tendencies to bias our beliefs via overconfidence, wishful thinking, and so on. Worse, our minds seem to have a natural tendency to convince us that we are aware of and have adequately corrected for such biases, when we have done no such thing."This may sound insulting, but one of the goals of this class is getting us to recognize that we're not as smart as we think we are. All of us. You. Me! That one. You again. Me again!

So I hope you'll join the campaign to end I'M-SPECIAL-ism.

Friday, April 13, 2012

Jock Math

Statistics in sports is all the rage lately. Here are some links on the topic.

- Statistical analysis can justify counterintuitive decisions, like going for it instead of punting on 4th down... though don't expect the fans to buy that fancy math learnin'.

- There are a lot of odd statistical myths about what happens on the day of the Super Bowl that deserve to be debunked.

- "Realistic Announcer Shouting How Kevin Durant Making His Last 4 Shots Has No Bearing On Whether He Will Make Next Shot"

- "Cornell Drains Fun Out Of Cinderella Run By Explaining How On A Long Enough Timeline The Improbable Becomes Probable"

- That radio show I love recently devoted an entire episode to probability:

- That other radio show I love ran a great 2-part series on the screening for diseases called "You Are Pre-Diseased":

- Here's a cool visualization of the president's promise to cut $100 million from the U.S. budget:

Labels:

as discussed in class,

audio,

links,

math,

psychological impediments,

videos

Thursday, April 12, 2012

The Importance of Being Stochastic

Statistical reasoning is incredibly important. The vast majority of advancements in human knowledge (all sciences, social sciences, medicine, engineering...) is the result of using some kind of math. If I had to recommend one other course that could improve your ability to learn in general, it'd be Statistics.

Anyway, here is a bunch of links:

Anyway, here is a bunch of links:

- Most of us are pretty bad at statistical reasoning.

- Here's a review of a decent book (The Drunkard's Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives) on our tendency to misinterpret randomness as if it's an intentional pattern.

- Controversial claim alert! This ability to see patterns where there are none may explain why so many of us believe in god (see section 5 in particular).

- It also may explain why we think small schools do a better job at educating students. They probably don't.

- What was that infinite monkey typewriter thing we were talking about in class?

- What's up with that recent recommendation that routine screenings for breast cancer should wait until your 50s rather than 40s? Math helps explain it.

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

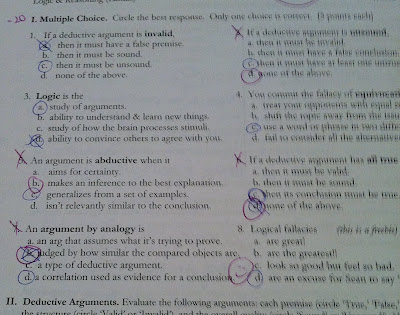

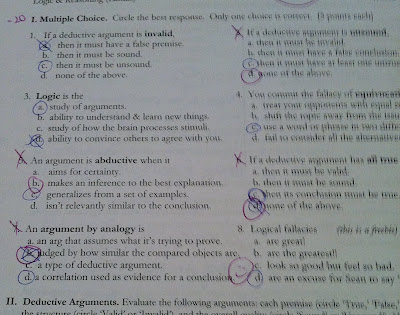

Change We Mistakenly Believe In

Here's a common example of confirmation bias and selective memory most of us have experienced: do you think we should stick with our first instinct when answering a test question? Most of us think we should. After all, so many of us remember lots of times where we initially circled the right answer, only to cross it out and choose another.

The problem with this is that research suggests that our first instincts are no more reliable than our second-guessing. Why does the myth persist? Well, we're more likely to remember the times we second-guessed and got it wrong than the times we second-guessed and got it right. Switching away from the right answer is just so frustrating that it's a more memorable event. So if I got back the following test...

...I'd probably only notice that I changed #6 and #7 to the wrong answer. I'd be much less likely to notice that I changed #1 and #3 to the right answer.

...I'd probably only notice that I changed #6 and #7 to the wrong answer. I'd be much less likely to notice that I changed #1 and #3 to the right answer.

The problem with this is that research suggests that our first instincts are no more reliable than our second-guessing. Why does the myth persist? Well, we're more likely to remember the times we second-guessed and got it wrong than the times we second-guessed and got it right. Switching away from the right answer is just so frustrating that it's a more memorable event. So if I got back the following test...

The Conspiracy Bug

Here's an article on a 9/11 conspiracy physicist that brings up a number of issues we're discussing in class (specifically appealing to authority and confirmation bias). I've quoted an excerpt of the relevant section on the lone-wolf semi-expert (physicist) versus the overwhelming consensus of more relevant experts (structural engineers):

While there are a handful of Web sites that seek to debunk the claims of Mr. Jones and others in the movement, most mainstream scientists, in fact, have not seen fit to engage them.And one more excerpt on reasons to be skeptical of conspiracy theories in general:

"There's nothing to debunk," says Zdenek P. Bazant, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northwestern University and the author of the first peer-reviewed paper on the World Trade Center collapses.

"It's a non-issue," says Sivaraj Shyam-Sunder, a lead investigator for the National Institute of Standards and Technology's study of the collapses.

Ross B. Corotis, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Colorado at Boulder and a member of the editorial board at the journal Structural Safety, says that most engineers are pretty settled on what happened at the World Trade Center. "There's not really disagreement as to what happened for 99 percent of the details," he says.

One of the most common intuitive problems people have with conspiracy theories is that they require positing such complicated webs of secret actions. If the twin towers fell in a carefully orchestrated demolition shortly after being hit by planes, who set the charges? Who did the planning? And how could hundreds, if not thousands of people complicit in the murder of their own countrymen keep quiet? Usually, Occam's razor intervenes.

Another common problem with conspiracy theories is that they tend to impute cartoonish motives to "them" — the elites who operate in the shadows. The end result often feels like a heavily plotted movie whose characters do not ring true.

Then there are other cognitive Do Not Enter signs: When history ceases to resemble a train of conflicts and ambiguities and becomes instead a series of disinformation campaigns, you sense that a basic self-correcting mechanism of thought has been disabled. A bridge is out, and paranoia yawns below.

Monday, April 9, 2012

Rationalizing Away from the Truth

A big worry that the confirmation and disconfirmation biases raise is the difficulty of figuring out what counts as successful, open-minded reasoning, versus what amounts to after-the-fact rationalization of preexisting beliefs. Here are some links on our tendency to rationalize rather than reason:

- Recent moral psychology suggests that we often simply rationalize our snap moral judgments. (Or worse: we actually undercut our snap judgments to defend whatever we want to do.)

- The great public radio show Radio Lab devoted an entire show to the psychology of our moral decision-making:

- Humans' judge-first, rationalize-later approach stems in part from the two competing decision-making styles inside our heads.

- For more on the dual aspects of our minds, I strongly recommend reading one of the best philosophy papers of 2008: "Alief and Belief" by Tamar Gendler.

- Here's a video dialogue between Gendler and her colleague (psychologist Paul Bloom) on her work:

Saturday, April 7, 2012

Friday, April 6, 2012

More to Forget

Here's more on the less of memory:

- Here's an overview on the way our memory is faulty by psychologist Gary Marcus. He's written a book called Kluge: The Haphazard Construction of the Human Mind.

- Even strong "flashbulb memories" like what you were doing on 9/11 are not very accurate.

- One leading expert on memory is psychologist Elizabeth Loftus (she's mentioned in our textbook). Here is a pair of articles that summarize her research on false memories, and here's a video of her presenting on it.

- Here's an article on the unreliability of eyewitness identification.

- Here's an article that suggests many jurors seem to prefer eyewitness testimony over forensic evidence. Given how unreliable our memories are, that's pretty scary. Here's a quote:

"Despite all our scientific know-how, jurors weighing life and death decisions still crave what Leone calls the 'human element:' the act of watching another person testify and deciding if they’re telling the truth.

"As these witnesses enter the courtroom, a hush often falls on the gallery. Jurors — bored by days of dry testimony given by well-rehearsed experts — lean forward in their seats, pens at the ready to take notes about what the eyewitness has to say. They have seen this moment on television, too, and it’s usually really, really interesting."

Thursday, April 5, 2012

Filling in Memory

Here's a section (pages 78-80) from psychologist Dan Gilbert's great book Stumbling on Happiness about how memory works:

The preview cuts off at the bottom of page 80. Here's the rest from that section:

Fine. Here's Dan Gilbert on The Colbert Report:

The preview cuts off at the bottom of page 80. Here's the rest from that section:

"...reading the words you saw. But in this case, your brain was tricked by the fact that the gist word--the key word, the essential word--was not actually on the list. When your brain rewove the tapestry of your experience, it mistakenly included a word that was implied by the gist but that had not actually appeared, just as volunteers in the previous study mistakenly included a stop sign that was implied by the question they had been asked but that had not actually appeared in the slides they saw.Too many words, Sean! Can't you just put up a video? You better make it funny, too!

"This experiment has ben done dozens of times with dozens of different word lists, and these studies have revealed two surprising findings. First, people do not vaguely recall seeing the gist word and they do not simply guess that they saw the gist word. Rather, they vividly remember seeing it and they feel completely confident that it appeared. Second, this phenomenon happens even when people are warned about it beforehand. Knowing that a researcher is trying to trick you into falsely recalling the appearance of a gist word does not stop that false recollection from happening."

Fine. Here's Dan Gilbert on The Colbert Report:

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

Course Evaluation

The course evaluation for this class is now open. Here are instructions on how to do this:

1. Go to http://cp.rowan.edu/cp/.

2. Click "Student Self-Service" icon.

3. Click "Access Banner Services - Secure Area - login required"

4. Enter User ID and PIN.

5. Click "Personal Information".

6. Click "Answer a Survey".

7. Click on one of the student evaluations for your classes.

8. Complete the student evaluation.

9. Click “Survey Complete” to submit your completed student evaluation.

10. Repeat for other Spring 2012 classes.

Tuesday, April 3, 2012

Misidentification

Here's an excellent, short video explanation of the unreliability of memory that ends with a dog licking peanut butter off a guy's face:

And here's a more serious video on the tragedy of misidentifying a suspect:

And here's a more serious video on the tragedy of misidentifying a suspect:

Labels:

as discussed in class,

links,

memory,

psychological impediments,

videos

Monday, April 2, 2012

Direct Experience

Here are two videos on stuff we're talking about in class this week. First, watch this:

Next, watch this:

Finally, here's an article on this issue. Still trust your direct experience?

Next, watch this:

Finally, here's an article on this issue. Still trust your direct experience?

Saturday, March 31, 2012

Deoderant Norms

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

fallacies,

links,

videos

Thursday, March 29, 2012

An Expert for Every Cause

Looking for links on appealing to authority? This is your post! First, here's an interesting article on a great question: How are those of us who aren't experts supposed to figure out the truth about stuff that requires expertise?

Not all alleged experts are actual experts. Here's a method to tell which experts are phonies (this article was originally published in the Chronicle of Higher Education).

We should judge experts who are into making predictions on how accurate their predictions turn out. Well, most experts are really bad at predicting.

It's important to check whether the person making an appeal to authority really knows who the authority is. That's why we should beware of claims that begin with "Studies show..."

And here's a Saturday Night Live sketch in which Christopher Walken completely flunks the competence test.

Not all alleged experts are actual experts. Here's a method to tell which experts are phonies (this article was originally published in the Chronicle of Higher Education).

We should judge experts who are into making predictions on how accurate their predictions turn out. Well, most experts are really bad at predicting.

It's important to check whether the person making an appeal to authority really knows who the authority is. That's why we should beware of claims that begin with "Studies show..."

And here's a Saturday Night Live sketch in which Christopher Walken completely flunks the competence test.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

fallacies,

links,

videos

Thursday, March 22, 2012

3/22 Class Canceled

I'm sick, so Thursday's class is canceled.

Our last two group presentations--groups #5 and #6--were scheduled for Thursday. They should now be prepared to present in class on Tuesday, March 27th.

Our last two group presentations--groups #5 and #6--were scheduled for Thursday. They should now be prepared to present in class on Tuesday, March 27th.

Labels:

assignments,

logistics,

more cats? calm down sean

Saturday, March 17, 2012

Midterm

The midterm will be held at the beginning of class on Tuesday, March 20th. It's worth 15% of your overall grade, and will cover everything we've done in class so far:

- definitions of 'logic,' 'reasoning,' and 'argument'

- evaluating arguments (Chapter 6)

- types of arguments:

-deductive (aim for certainty, are valid/invalid and sound/unsound) (Chapter 8)

-inductive (generalizing from examples, are evaluated based how large and representative the examples in the premises are) (Chapter 7)

-args about cause/effect (correlation vs. causation) (Chapter 7)

-args by analogy (evaluated in terms of how similar the things compared are, and how relevant the similarities are to the conclusion being drawn) (Chapter 7)

-abductive (inferences to the best explanation, evaluated in terms of coherence with background theories, simplicity, predictive power, falsifiability, etc.) (Chapter 12) - the 11 fallacies covered in class so far (Chapter 5)

Labels:

abductive,

as discussed in class,

assignments,

deductive,

fallacies,

inductive,

logistics,

more cats? calm down sean

Thursday, March 15, 2012

Begging the Hot

- Here's a psychology paper (pdf) about the success of offering question-begging reasons to use a copier. The psychologists dubbed these nonsense reasons "placebic information."

- Warning: my explanation of that study is a bit oversimplified. Here's an excellent explanation of what the study actually showed in the service of a larger point: even the most careful of us unintentionally distort and oversimplify the results of scientific studies.

- Here's a video for Mims's logically delicious song "This is Why I'm Hot":

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

fallacies,

links,

videos

Tuesday, March 13, 2012

Let's Be Diplomatic: Straw Person

Here's some stuff on the straw man fallacy:

Here's some stuff on the straw man fallacy:- Politicians love to distort their opponents' positions. Even Obama does it.

- Politicians aren't alone: we do it, too. Often we distort arguments for claims we disagree with without even realizing it. This is because we have trouble coming up with good reasons supporting a conclusion that we think is false, so we have a tendency to make up bad reasons and attribute them to our opponents.

- Hire your own professional straw man!

- Here's the Critical Thinker's video explanation of the straw figure fallacy:

- I recommend the Critical Thinker's podcast.

Clever.

Sunday, March 11, 2012

That's an Ad Hominem, Jerk

Here are some links on the ad hominem (personal attack) fallacy:

- Sure, some critics of Obama are racist, but does that mean we can dismiss their arguments? As much as we might want to, logically, no we cannot!

- Some variants on the personal attack: tu quoque (hypocrite!) and guilt by association (she hangs around bad people!).

- I should note that tu quoque isn't always fallacious reasoning.

- "The ad hominem rejoinders—ready the ad hominem rejoinders!"

- Remember our rallying cry: "STUPID PEOPLE SOMETIMES SAY SMART THINGS."

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

fallacies,

links,

videos

Tuesday, March 6, 2012

Fallacies, Fallacies, Everywhere

Looking for links on fallacies and equivocation? This is your post! First, there's a nice series of short articles on a bunch of different fallacies, including many that aren't in our book.... but also an entry on equivocation.

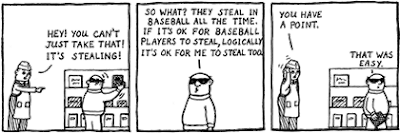

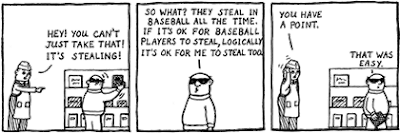

Speaking of, my best friend the inter-net has some nice examples of the fallacy of equivocation. Here is one good one:

Speaking of, my best friend the inter-net has some nice examples of the fallacy of equivocation. Here is one good one:

Saturday, March 3, 2012

Homework #2: Fallacies

Homework #2 is due at the beginning of class on Thursday, March 8th. The assignment is to complete the worksheet on fallacies that I'll hand out in Tuesday's class. If you don't get a copy, you can click here to download a .pdf version of the worksheet. Homework #2 is worth 30 points (3% of your overall grade).

Thursday, March 1, 2012

Ockham Weeps

Labels:

abductive,

comment begging,

cultural detritus

Wednesday, February 29, 2012

Fun Tuesday #1: Belief and Evidence

You still have a chance to do the Fun Tuesday assignment if you missed it in class yesterday. Just print out the following worksheet (pdf) and fill in your answer for each statement.

(There will be some points off if your absence on Tuesday was unexcused.)

(There will be some points off if your absence on Tuesday was unexcused.)

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

links,

logistics

Tuesday, February 28, 2012

Murder on the Abductive Express

I think abductive reasoning is the most effective tool we have when faced with the myriad uncertain, ambiguous issues and decisions that everyday life throws our way. Here are some links:

- Here's a paper (pdf) that explains why I disagree with our textbook's explanation of the scientific method. It's important to consider and test multiple possible explanations rather than a single hypothesis.

- (NOTE: Platt uses the word "inductive" in a more general way than we do in class, to refer to any non-deductive kind of reasoning--that is, arguments that don't attempt to absolutely prove their conclusion.)

- I'm 75% through reading this book: Inference to the Best Explanation by Peter Lipton.

- Remember when I was talking about Einstein's theory of general relativity having predictive power? This is what I had in mind.

- Everything you ever wanted to know about William of Ockham and his famous razor.

- Lastly, here's a dinosaur comic murder mystery.

Friday, February 24, 2012

Child Abduction

Psychologist Alison Gopnik gave a great TED talk recently on how children are natural abductive reasoners; playing and making pretend is often about coming up with and testing various hypotheses. Here's the talk:

Gopnik's book, The Philosophical Baby, is great.

Gopnik's book, The Philosophical Baby, is great.

Labels:

abductive,

as discussed in class,

links,

videos

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

Correlatious

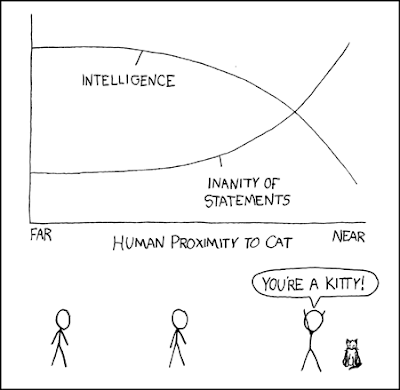

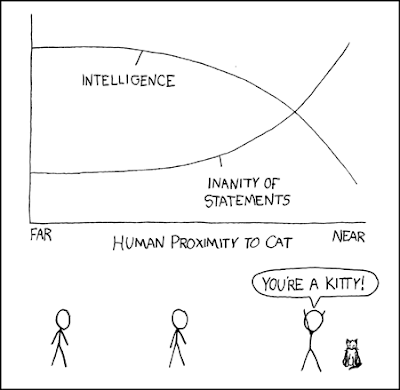

Here's yet another stick-figure comic (for those keeping track, that's five total on the blog so far). This one's about correlation.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

inductive

Saturday, February 18, 2012

The Full Moon Myth

We talked about this on Tuesday: Scientific American has a nice article examining the widely-held belief that the full moon causes strange behavior. Research suggests the full moon doesn't have this effect:

We talked about this on Tuesday: Scientific American has a nice article examining the widely-held belief that the full moon causes strange behavior. Research suggests the full moon doesn't have this effect:"By combining the results of multiple studies and treating them as though they were one huge study—a statistical procedure called meta-analysis—[scientists] have found that full moons are entirely unrelated to a host of events, including crimes, suicides, psychiatric problems and crisis center calls. In their 1985 review of 37 studies entitled 'Much Ado about the Full Moon,' which appeared in one of psychology’s premier journals, Psychological Bulletin, Rotton and Kelly humorously bid adieu to the full-moon effect and concluded that further research on it was unnecessary."One reason the belief persists is a set of natural human cognitive biases in which we perceive correlations where no such correlations exist:

"Illusory correlations result in part from our mind’s propensity to attend to—and recall—most events better than nonevents. When there is a full moon and something decidedly odd happens, we usually notice it, tell others about it and remember it. We do so because such co-occurrences fit with our preconceptions. ... In contrast, when there is a full moon and nothing odd happens, this nonevent quickly fades from our memory. As a result of our selective recall, we erroneously perceive an association between full moons and myriad bizarre events."We'll be discussing these biases more when we study arguments about causes. Here's a cool video by psychological Dan Gilbert on our mistaken expectations:

Thursday, February 16, 2012

Our Inductive Minds

Here are some more thoughtful links on inductive reasoning.

- What are the benefits and dangers of generalizations?

- What makes stereotyping illogical?

- Beware: we often make snap judgments before thinking through things. Then when we do think through things, we just wind up rationalizing our snap judgments.

Friday, February 10, 2012

Quiz You Once, Shame on Me

The first quiz will be held at the beginning of class on Tuesday, February 14th. You will have about 25 minutes to take it.

There will be a multiple choice section, a section on understanding arguments, a section on evaluating deductive arguments, and a section where you provide examples of specific kinds of arguments. Basically, it will look like a mix of the homework, extra credit, and group work we've done in class so far.

The quiz is on what we have discussed in class from chapters 6, 8, and part of 7 of the textbook. Specifically, here's a lot of the stuff we've talked about in class so far that I expect you to know for the quiz:

There will be a multiple choice section, a section on understanding arguments, a section on evaluating deductive arguments, and a section where you provide examples of specific kinds of arguments. Basically, it will look like a mix of the homework, extra credit, and group work we've done in class so far.

The quiz is on what we have discussed in class from chapters 6, 8, and part of 7 of the textbook. Specifically, here's a lot of the stuff we've talked about in class so far that I expect you to know for the quiz:

- definitions of: logic, reasoning, argument, support, sound, valid, deductive, inductive

- understanding arguments

- evaluating arguments (truth and support!)

- deductive args (valid & sound)

- inductive args (there will only be a little on this)

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

deductive,

inductive,

logistics

Inductioneering

Here are two dumb things about inductive arguments. First, a video of comedian Lewis Black describing his failure to learn from experience every year around Halloween:

Next, this stick figure comic offers a pretty bad argument. Why is it bad? (Let us know in the comments!)

Next, this stick figure comic offers a pretty bad argument. Why is it bad? (Let us know in the comments!)

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

inductive,

videos

Tuesday, February 7, 2012

Group Presentations: 9:25 a.m. Class

Here are the assigned groups for the group presentations on fallacies for the 9:25 a.m. class, along with your topics and the tentative date of each presentation (those dates may be pushed back):

During our section on fallacies, groups of 4-5 students will present short lessons on two specific fallacies that their members have researched on their own.

Groups are free to choose how to present their topic to the rest of the class. Be creative! Think about puppets, posters, cartoons, songs, skits, handouts, whatever. Part of your grade will be based on how creative your presentation is. Remember, though, that you are expected to teach these fallacies to the rest of the class. Although they will have read about your fallacies in our textbook, the rest of class will probably not be as familiar with the material you are presenting as your group is. Here are some helpful suggestions of things to include in your presentation:

The presentation is worth 150 points (15% of your overall grade). Except in unusual circumstances, each group member shall receive the same grade. There will not be any time set aside in class for groups to research and prepare for their presentation, so you should meet outside class to work on this presentation.

- Ad Hominem & Appeal to Force (February 28th): Dale, Jeff, Kenniqua, Yasmine, Zach

- Appeal to Pity & Popular Appeal (February 28th): Brenda, Jon, José, Sean

- Appeal to Ignorance & Begging the Question (March 1st): Courtney, Frank, Kevin, Steve W.

- Straw Man & Red Herring (March 1st): Chaz, Donnie, Giselle, Jason, Samantha

- Appeal to Authority & False Dilemma (March 20th): Daniel, Jasmaine, Joey, John, Maggie

- Slippery Slope & The Naturalistic Fallacy (March 20th): Akin, Beth, Brittany, Heather, Stephen C.

During our section on fallacies, groups of 4-5 students will present short lessons on two specific fallacies that their members have researched on their own.

Groups are free to choose how to present their topic to the rest of the class. Be creative! Think about puppets, posters, cartoons, songs, skits, handouts, whatever. Part of your grade will be based on how creative your presentation is. Remember, though, that you are expected to teach these fallacies to the rest of the class. Although they will have read about your fallacies in our textbook, the rest of class will probably not be as familiar with the material you are presenting as your group is. Here are some helpful suggestions of things to include in your presentation:

- DEFINITION: A formal definition of each fallacy

- A slow, clear explanation in plain English of what those definitions mean

- EXAMPLES: Lots of specific examples of arguments that commit each fallacy

- Explanations of how it is that these example arguments commit the fallacy

- WHY BAD?: An explanation of why each fallacy is a mistake in reasoning

The presentation is worth 150 points (15% of your overall grade). Except in unusual circumstances, each group member shall receive the same grade. There will not be any time set aside in class for groups to research and prepare for their presentation, so you should meet outside class to work on this presentation.

Monday, February 6, 2012

Group Presentations: 8:00 a.m. Class

Here are the assigned groups for the group presentations on fallacies for the 8:00 a.m. class, along with your topics and the tentative date of each presentation (those dates may be pushed back):

During our section on fallacies, groups of 4-5 students will present short lessons on two specific fallacies that their members have researched on their own.

Groups are free to choose how to present their topic to the rest of the class. Be creative! Think about puppets, posters, cartoons, songs, skits, handouts, whatever. Part of your grade will be based on how creative your presentation is. Remember, though, that you are expected to teach these fallacies to the rest of the class. Although they will have read about your fallacies in our textbook, the rest of class will probably not be as familiar with the material you are presenting as your group is. Here are some helpful suggestions of things to include in your presentation:

The presentation is worth 150 points (15% of your overall grade). Except in unusual circumstances, each group member shall receive the same grade. There will not be any time set aside in class for groups to research and prepare for their presentation, so you should meet outside class to work on this presentation.

- Ad Hominem & Appeal to Force (February 28th): Brandon, Christie, Felix, John

- Appeal to Pity & Popular Appeal (February 28th): Ashley, Ryan, Stephanie, Tevin

- Appeal to Ignorance & Begging the Question (March 1st): Evan, Jim, Joshani, Katie

- Straw Man & Red Herring (March 1st): Kayla, Leanne, Michael, Nicole, Victoria

- Appeal to Authority & False Dilemma (March 20th): Ericca, Jordan, Luke, Sheena

- Slippery Slope & The Naturalistic Fallacy (March 20th): Alberto, Frank, Ileana, Kristin

During our section on fallacies, groups of 4-5 students will present short lessons on two specific fallacies that their members have researched on their own.

Groups are free to choose how to present their topic to the rest of the class. Be creative! Think about puppets, posters, cartoons, songs, skits, handouts, whatever. Part of your grade will be based on how creative your presentation is. Remember, though, that you are expected to teach these fallacies to the rest of the class. Although they will have read about your fallacies in our textbook, the rest of class will probably not be as familiar with the material you are presenting as your group is. Here are some helpful suggestions of things to include in your presentation:

- DEFINITION: A formal definition of each fallacy

- A slow, clear explanation in plain English of what those definitions mean

- EXAMPLES: Lots of specific examples of arguments that commit each fallacy

- Explanations of how it is that these example arguments commit the fallacy

- WHY BAD?: An explanation of why each fallacy is a mistake in reasoning

The presentation is worth 150 points (15% of your overall grade). Except in unusual circumstances, each group member shall receive the same grade. There will not be any time set aside in class for groups to research and prepare for their presentation, so you should meet outside class to work on this presentation.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

fallacies,

logistics

Sunday, February 5, 2012

An Argument's Support

One of the trickier concepts to understand in this course is the structure (or support) of an argument. This is a more detailed explanation of the term. If you've been struggling to understand this term, the following might help you.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises provide us with enough information for us to figure out the conclusion from them. In other words, the premises, if they were true, would logically show us that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures are such that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Arguments (Valid)

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion will also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows will be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, are you able to figure out from the premises that the conclusion is also true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths gives you a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Arguments (Invalid)

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – the premises don’t give you enough information. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting dogs take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises provide us with enough information for us to figure out the conclusion from them. In other words, the premises, if they were true, would logically show us that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures are such that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Arguments (Valid)

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion will also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows will be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, are you able to figure out from the premises that the conclusion is also true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths gives you a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Arguments (Invalid)

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – the premises don’t give you enough information. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting dogs take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)